Introduction to MRI

MRI Basics

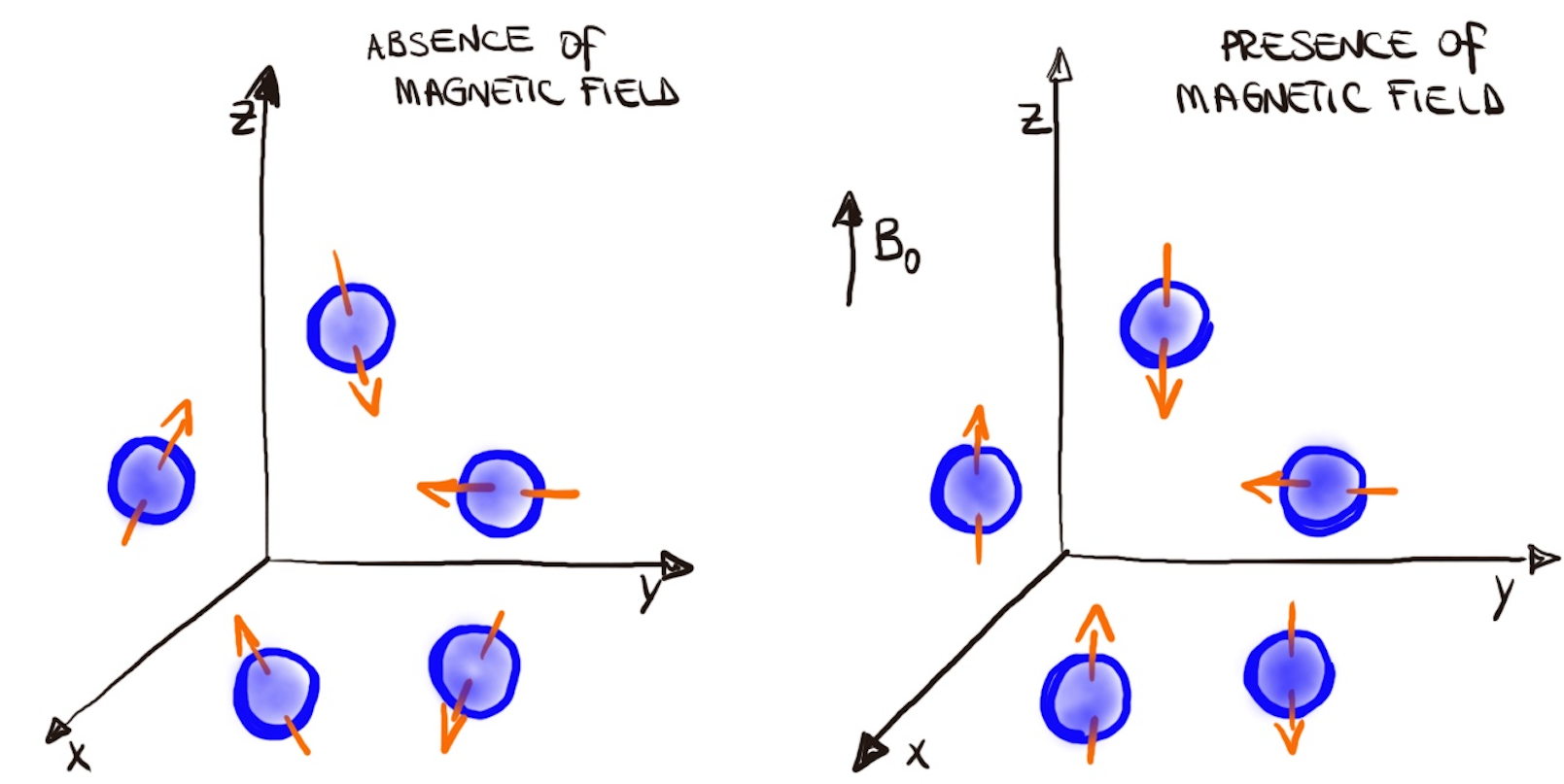

Atoms are made up of a nucleus and a shell of electrons. Inside the nucleus, there are protons, which have a positive electrical charge. These protons are constantly spinning around an axis, which creates a spin (see figure). Because protons are moving electrical charges, they generate an electrical current. This current creates a magnetic field, making each proton act like a tiny bar magnet with its own magnetic field. When protons are placed in an MRI scanner, they align with the external magnetic field. There are two ways they can align:- Parallel to the magnetic field (lower energy state)

- Anti-parallel to the magnetic field (higher energy state)

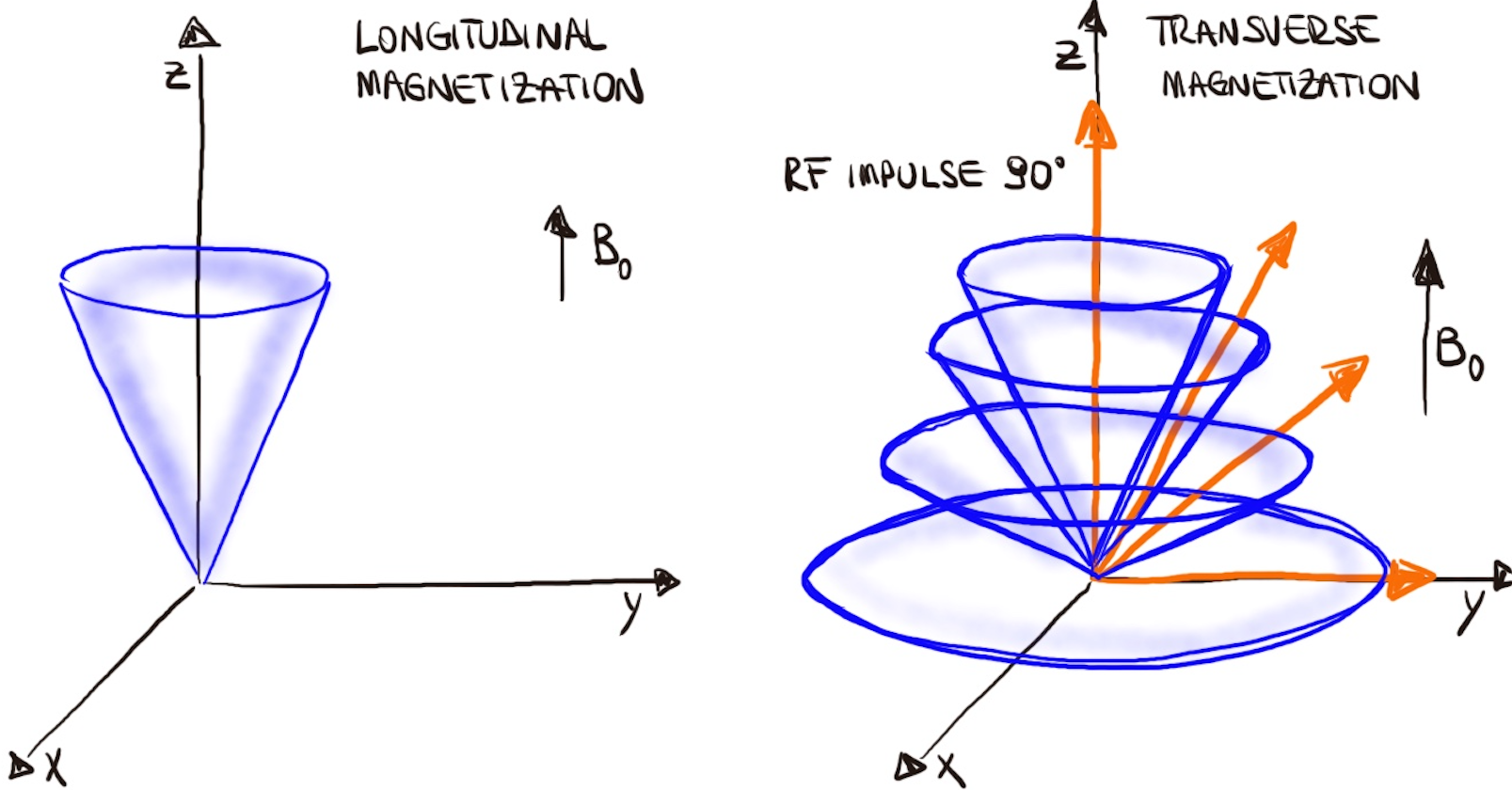

- Longitudinal Magnetization Decreases: More protons align anti-parallel, canceling out some of the parallel protons.

- Transversal Magnetization Forms: The RF pulse synchronizes the protons, causing them to precess together.

Key Terms in MRI:

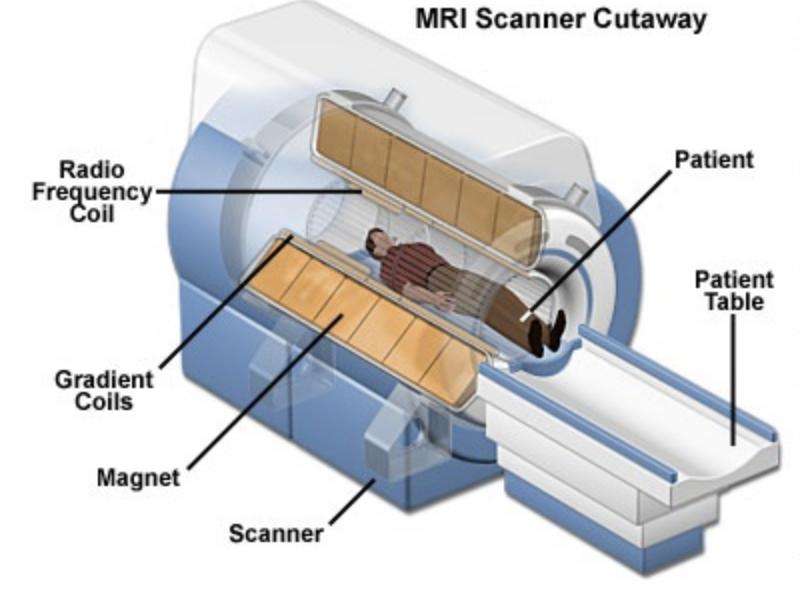

- Magnet: The core component of the MRI scanner generating a powerful magnetic field to align the protons in the body. The strength of the magnet is typically measured in tesla (T) with common strengths ranging from 1.5T to 3T in clinical settings and up to 7T or more in research settings. Higher magnetic field strengths (e.g., 7T) provide better signal-to-noise ratio and spatial resolution, allowing for more detailed and precise imaging of the brain and other organs.

- Radiofrequency Coils: These coils transmit and receive radiofrequency pulses that perturb and detect the protons' magnetic alignment. They come in various shapes and sizes tailored for specific body parts or imaging purposes.

- Resonance: This phenomenon occurs when the RF pulse matches the protons' frequency, allowing them to absorb energy from the radio waves. This is where the term "resonance" in "magnetic resonance" comes from.

- Proton Resonance: Hydrogen protons in the body align with a magnetic field and then resonate when exposed to radiofrequency pulses (RF).

- Gradients: Gradient magnets are used to spatially encode the signals received from the protons, allowing for the construction of an image.

- Gradient Coils: These coils create variable magnetic fields that allow for spatial encoding of the MRI signal. They are essential for slice selection, spatial resolution, and imaging speed.

- Computer System: The MRI scanner’s computer system controls the hardware, processes the signals received from the radiofrequency coils, and reconstructs the images for display and analysis. It includes powerful processors and advanced software algorithms for image reconstruction and enhancement.

2. MRI Protocols and Sequences

Protocol Selection:

Choosing the right MRI protocols and sequences is crucial for obtaining the best possible images for the clinical question or research objective. For instance, T1-weighted imaging is ideal for anatomical detail, while T2-weighted imaging is better for identifying pathologies such as edema or tumors. The choice of protocol should consider tissue type, desired contrast, and anatomical area. Additionally, standardized acquisition parameters and logical axioms for different MRI types are essential to ensure reproducibility and interoperability.

-

Spin Echo (SE)

- T1-Weighted Imaging: Highlights fat and provides clear images of the brain's anatomy.

- T2-Weighted Imaging: Highlights fluid and is useful for detecting edema and inflammation.

-

Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI)

- Conventional DWI: Detects the movement of water molecules in tissue, helpful in identifying acute stroke and other brain pathologies.

- Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI): Maps the orientation and integrity of white matter tracts in the brain.

-

Inversion Recovery (IR)

- FLAIR (Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery): Suppresses fluids, enhancing the visibility of lesions.

- DIR (Double Inversion Recovery): Suppresses both CSF and white matter signals, making it easier to detect cortical lesions.

-

Perfusion Imaging

- Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL): Non-invasively measures blood flow in tissues, useful for assessing perfusion in various brain regions.

-

Functional MRI (fMRI)

- BOLD (Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent): Measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood oxygen levels, commonly used in functional brain mapping.

-

Gradient Echo (GRE)

- T2 (T2 Star-Weighted Imaging): Sensitive to magnetic field inhomogeneities, useful for detecting hemorrhage or iron deposition.

- SWI (Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging): Enhances sensitivity to blood products and other paramagnetic substances, useful in detecting microbleeds and vascular abnormalities.

Structural MRI:

Structural MRI (sMRI) utilizes magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of the brain's anatomy. This technique allows for high-resolution examination of brain structures, providing essential information about the size, shape, and integrity of various brain regions.Techniques: cortical thickness (CT) [1], diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) [2], surface-based morphometry (SBM) [3,4], and voxel-based morphometry (VBM) [5,6].

Applications: It is particularly useful for identifying abnormalities such as tumors, brain injuries, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Example: A study using VBM to identify brain volume reductions in patients with Alzheimer's disease.

Functional MRI:

Functional MRI (fMRI) detects changes in blood oxygen levels (BOLD signal) to visualize and measure brain activity in real time [7,8]. There are two main types of fMRI:

Techniques:

- Task-based fMRI: Involves participants performing specific tasks while their brain activity is measured, providing insights into brain function related to cognitive and motor tasks [9].

- Resting-state fMRI: Measures brain activity when a person is not performing any explicit tasks, capturing the brain's intrinsic functional connectivity [10].

Applications: It can be used in cognitive and behavioral studies, mapping brain functions, and pre-surgical planning.

Example: Task-based fMRI identifying regions activated during language tasks in epilepsy patients for surgical planning.

Diffusion MRI:

Diffusion MRI maps the local diffusion properties of the water molecules in biological tissues [11].

Techniques:

- DWI (Diffusion Weighted Imaging): Detects differences in the degree of movement of water molecules (speed) [12].

- DTI (Diffusion Tensor Imaging): Maps the diffusion of water along white matter tracts. Reports information on the degree of diffusion (speed) + main (preferential) direction of movement of water molecules [2,13].

- DSI (Diffusion Spectrum Imaging) and QBI (Imaging q-ball): Captures more complex diffusion patterns [14,15].

Computational Analysis: Tools like FSL, MRtrix, and DSI Studio for tractography and tensor analysis.

Example: DTI used to map white matter changes in patients with multiple sclerosis.